Spinning in sheet metal, often referred to as metal spinning or spin forming, is a metalworking process by which a flat metal disc or tube is rotated at high speed and formed into an axially symmetric part. This technique, steeped in both historical tradition and modern industrial application, leverages rotational forces and controlled deformation to shape metal with precision and efficiency. Employed across industries ranging from aerospace to decorative arts, metal spinning stands as a versatile and cost-effective method for producing components such as cones, cylinders, hemispheres, and complex contoured shapes. This article delves into the intricacies of the process, its history, mechanics, materials, tooling, applications, and scientific underpinnings, offering a comprehensive exploration suitable for both novices and experts in materials engineering.

The origins of metal spinning trace back to ancient civilizations, with evidence of rudimentary forms appearing in Egyptian and Chinese artifacts dating as early as 1400 BCE. Artisans of these periods used simple tools to shape metals like copper and bronze into vessels and ornaments, relying on manual force and basic rotational devices. By the Middle Ages, the craft evolved with the advent of the lathe, a pivotal invention that mechanized rotation and enhanced precision. The Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries marked a turning point, as steam-powered machinery and later electric lathes enabled mass production and the use of harder metals like steel. Today, computer numerical control (CNC) technology has revolutionized metal spinning, integrating digital precision with traditional techniques to meet the demands of modern engineering.

Fundamentally, metal spinning involves clamping a metal blank—typically a circular sheet or preformed tube—against a mandrel, a solid form that defines the final shape. The blank is then rotated at speeds ranging from 300 to 1,500 revolutions per minute (RPM), depending on the material, thickness, and desired geometry. A forming tool, often a roller or spoon-shaped instrument, applies localized pressure to the spinning metal, gradually deforming it over the mandrel. This process can be performed manually by skilled operators or automated using CNC systems, which offer repeatability and complex tool paths. The deformation occurs incrementally, with the metal flowing plastically under compressive and shear forces, a phenomenon governed by the principles of material science and metallurgy.

The mechanics of metal spinning are rooted in the plastic deformation of metals, a process where the material exceeds its yield strength but remains below its ultimate tensile strength. This balance ensures that the metal stretches and flows without fracturing. The stress-strain behavior of the metal is critical, as it dictates how the material responds to the applied forces. Ductility, the ability of a material to undergo significant plastic deformation before rupture, is a key property in spinning. Metals with high ductility, such as aluminum, copper, and mild steel, are ideal candidates, while brittle materials like cast iron are generally unsuitable. The strain rate, influenced by the spinning speed and tool pressure, further affects the outcome, with higher rates potentially leading to work hardening—a strengthening mechanism where dislocations in the metal’s crystal lattice multiply and impede further deformation.

Temperature plays a subtle yet significant role in metal spinning. Most spinning occurs at room temperature, classified as cold forming, which preserves the metal’s grain structure and mechanical properties. However, for thicker blanks or less ductile materials like titanium or stainless steel, hot spinning may be employed. In this variant, the metal is heated to a temperature below its recrystallization point—typically between 300°C and 800°C—reducing its yield strength and enhancing formability. The trade-off, however, is potential grain growth or oxidation, which can alter the material’s microstructure and surface quality. Cold spinning, by contrast, minimizes such effects, making it preferable for thin-gauge sheets and high-precision components.

The choice of material profoundly influences the spinning process and its outcomes. Aluminum, with its low density (2.7 g/cm³), excellent corrosion resistance, and high ductility (elongation up to 40%), is a mainstay in spinning applications, from cookware to aerospace nose cones. Copper, prized for its thermal conductivity (401 W/m·K) and malleability, finds use in decorative items and electrical components. Mild steel, with a yield strength of approximately 250 MPa and moderate ductility, offers a balance of strength and formability, suitable for automotive parts. Stainless steel, with its chromium content (typically 10-20%) imparting corrosion resistance, poses challenges due to its higher strength (yield strength ~300-600 MPa) and tendency to work harden, often necessitating slower speeds or heated spinning. Table 1 below provides a detailed comparison of these materials’ properties relevant to spinning.

Table 1: Material Properties for Metal Spinning

| Material | Density (g/cm³) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | Spinning Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum (1100) | 2.7 | 34 | 90 | 35-40 | 222 | Excellent, highly ductile |

| Copper (C11000) | 8.96 | 70 | 220 | 40-50 | 401 | Excellent, soft and malleable |

| Mild Steel | 7.85 | 250 | 400 | 20-30 | 51.9 | Good, moderate ductility |

| Stainless Steel (304) | 8.0 | 300 | 600 | 40-60 | 16.2 | Moderate, work hardens |

| Titanium (Grade 2) | 4.51 | 275 | 345 | 20-25 | 21.9 | Challenging, requires heat |

Tooling in metal spinning is another critical factor, encompassing both the mandrel and the forming tool. The mandrel, typically made of steel, aluminum, or wood (for low-volume production), must withstand the forces of deformation without deflecting. Its surface finish directly affects the final part’s quality, with polished mandrels yielding smoother finishes. Forming tools vary in design: rollers, with diameters of 25-100 mm, distribute pressure evenly and are ideal for automated spinning, while pointed tools allow for intricate detailing in manual operations. Tool materials range from hardened steel (Rockwell hardness ~60 HRC) to carbide-tipped variants, chosen based on the workpiece material and production volume. Lubrication, such as molybdenum disulfide or wax, reduces friction between the tool and metal, minimizing galling and extending tool life.

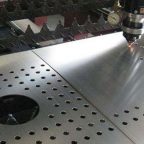

The process itself can be categorized into three main types: conventional spinning, shear spinning, and tube spinning. Conventional spinning, the most common, involves stretching the metal over the mandrel without significantly altering its thickness, relying heavily on the operator’s skill or CNC programming. Shear spinning, also known as power spinning, reduces the metal’s thickness by applying intense shear forces, producing lightweight, high-strength parts like missile cones. Tube spinning, a subset, shapes cylindrical preforms into longer or thinner tubes, often used in piping or structural components. Each method has distinct force dynamics and thickness outcomes, as outlined in Table 2.

Table 2: Comparison of Metal Spinning Techniques

| Technique | Thickness Change | Force Application | Typical Applications | Skill Level Required | Equipment Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | Minimal (<10%) | Compressive, incremental | Bowls, lampshades, hubs | High (manual), Low (CNC) | Moderate |

| Shear Spinning | Significant (20-70%) | Shear, high pressure | Rocket nozzles, cones | Moderate | High |

| Tube Spinning | Variable (5-50%) | Radial, axial | Pipes, pressure vessels | Moderate | High |

The forces involved in spinning are a complex interplay of tangential, radial, and axial components. In conventional spinning, the tangential force drives the rotation, while radial pressure from the tool induces deformation. Axial forces, particularly in shear spinning, thin the metal by displacing material outward. These forces can be quantified using the following simplified equation for tangential stress in a spinning disc:

σt=(ρω2r2)/2

where:

- σt \sigma_t σt = tangential stress (Pa),

- ρ \rho ρ = material density (kg/m³),

- ω \omega ω = angular velocity (rad/s),

- r r r = radius from the center (m).

For a 1 mm thick aluminum disc spinning at 500 RPM (52.36 rad/s) with a radius of 0.1 m, the tangential stress approximates 370 kPa, well below the material’s yield strength, indicating that additional tool pressure is necessary for deformation. This calculation underscores the balance between rotational dynamics and applied force, a cornerstone of spinning’s scientific foundation.

Applications of metal spinning span a wide spectrum, reflecting its adaptability. In aerospace, shear-spun components like rocket nose cones and fuel tank domes benefit from the process’s ability to create seamless, lightweight structures. Automotive industries utilize spun parts such as wheel rims and exhaust cones, valuing the technique’s cost efficiency for small to medium batches. Household goods—think mixing bowls, pots, and lamp reflectors—demonstrate spinning’s accessibility to consumer markets. Even artistic endeavors, from sculptural forms to musical instrument bells, leverage the process’s flexibility with soft metals like brass (Cu-Zn alloys). The diversity of these applications highlights spinning’s role as a bridge between artisanal craftsmanship and industrial precision.

One of spinning’s chief advantages is its cost-effectiveness for low-volume production. Unlike stamping or deep drawing, which require expensive dies and presses, spinning uses relatively simple tooling, with mandrels often costing 10-20% of a comparable die set. Setup times are short, and the process accommodates design changes with minimal retooling—a boon for prototyping. However, for high-volume runs (>10,000 units), spinning loses ground to stamping due to slower cycle times (typically 1-5 minutes per part versus seconds for stamping). Material utilization is another strength, as spinning generates little waste compared to subtractive methods like machining, aligning with sustainable manufacturing principles.

Challenges in metal spinning include wrinkling, thinning, and springback. Wrinkling occurs when compressive stresses exceed the material’s buckling resistance, often in thin sheets (<0.5 mm) or large-diameter blanks. Adjusting tool pressure or using stabilizing follower rests mitigates this. Thinning, inherent in shear spinning, must be controlled to avoid weak spots, requiring precise force calibration. Springback, the elastic recovery of the metal after forming, complicates dimensional accuracy, particularly in high-strength alloys. Annealing—heat treatment to relieve internal stresses—can reduce springback, though it adds a process step.

Surface finish and tolerances are also critical considerations. Spinning typically achieves finishes of 1.6-3.2 µm Ra (roughness average), adequate for many applications but coarser than machined surfaces (<0.8 µm Ra). Tolerances range from ±0.1 mm in CNC spinning to ±0.5 mm in manual operations, sufficient for structural parts but less so for precision fits. Post-processing, such as polishing or trimming, can refine these attributes, though it increases costs.

The metallurgy of spun parts reveals fascinating insights into grain structure and mechanical properties. Cold spinning refines the grain size through work hardening, enhancing strength but reducing ductility—a phenomenon quantifiable via the Hall-Petch relationship:

σy=σ0+kd−1/2

where:

- σy \sigma_y σy = yield strength (MPa),

- σ0 \sigma_0 σ0 = friction stress (MPa),

- k k k = strengthening coefficient (MPa·m^{1/2}),

- d d d = grain diameter (m).

For aluminum, a reduction in grain size from 50 µm to 20 µm might increase yield strength by 20-30 MPa, a tangible benefit for load-bearing components. Hot spinning, conversely, may coarsen grains, softening the metal but improving formability.

Modern advancements in metal spinning center on automation and simulation. CNC spinning lathes, equipped with multi-axis control and real-time feedback, achieve complex geometries—think parabolic reflectors or multi-stepped cones—with sub-millimeter precision. Finite element analysis (FEA) simulates deformation, predicting stress distributions, thinning patterns, and potential defects before production begins. These tools reduce trial-and-error, optimizing parameters like tool path, speed, and pressure. Industry 4.0 integration, with sensors monitoring force and temperature, further enhances process control, pushing spinning into high-tech domains.

Environmental impacts of metal spinning are relatively benign compared to casting or forging. Energy consumption is moderate, with CNC lathes drawing 5-15 kW depending on size, far less than the 100+ kW of industrial furnaces. Material waste is minimal, and lubricants are often biodegradable. However, noise from high-speed rotation (70-90 dB) and potential dust from tool wear necessitate workplace mitigations like sound barriers and ventilation.

To expand this discussion to a scientific depth, consider the kinematics of the spinning tool. The roller’s contact point traces a helical path over the blank, with its velocity vector comprising tangential (vt=ωr v_t = \omega r vt=ωr) and radial (vr v_r vr) components. The radial velocity depends on the tool feed rate, typically 1-5 mm/s in CNC systems. The resultant shear strain rate, γ˙ \dot{\gamma} γ˙, influences flow stress and can be approximated as:

γ˙=vr/h

where h h h is the instantaneous thickness. For a 1 mm thick sheet and 2 mm/s feed, γ˙≈2 s−1 \dot{\gamma} \approx 2 \, s^{-1} γ˙≈2s−1, a moderate rate that avoids excessive hardening in ductile metals.

Fatigue performance of spun parts is another area of interest. The cold-worked surface layer, rich in compressive residual stresses, enhances fatigue life by resisting crack initiation—a principle exploited in aerospace components subjected to cyclic loading. Testing per ASTM E466 standards might reveal a 20-50% improvement in endurance limit over annealed counterparts, depending on the alloy and spinning conditions.

Maximize Tooling and CNC Metal Spinning Capabilities.

At BE-CU China Metal Spinning company, we make the most of our equipment while monitoring signs of excess wear and stress. In addition, we look into newer, modern equipment and invest in those that can support or increase our manufacturing capabilities. Our team is very mindful of our machines and tools, so we also routinely maintain them to ensure they don’t negatively impact your part’s quality and productivity.

Talk to us today about making a rapid prototype with our CNC metal spinning service. Get a direct quote by chatting with us here or request a free project review.

BE-CU China CNC Metal Spinning service include : CNC Metal Spinning,Metal Spinning Die,Laser Cutting, Tank Heads Spinning,Metal Hemispheres Spinning,Metal Cones Spinning,Metal Dish-Shaped Spinning,Metal Trumpet Spinning,Metal Venturi Spinning,Aluminum Spinning Products,Stainless Steel Spinning Products,Copper Spinning Products,Brass Spinning Products,Steel Spinning Product,Metal Spinnin LED Reflector,Metal Spinning Pressure Vessel,